Posted Mar 6, 2016 by Martin Armstrong

Mixing Religion and politics has been a major problem throughout history. It has never worked when one religion attempts to force upon others their particular belief. The Freedom of Religion, a cornerstone of the American Constitution, was the product of reason and understanding history. Religion has been responsible for more bloodshed throughout history than anything else just as we see ISIS today or the English Civil War, Protestant Reformation, and the takeover of Rome by Christianity. Examples of such chaos when one religion attempts to force itself upon the majority extends back into Roman times. According to the Historia Augusta (Heliogab. 1.6), when the Emperor Elagabalus (218-222AD) came to power, he had been the high priest in the city of Emesa which is Homs today in Syria. He then imposed his religion upon Rome and the Senate.

The Emesa region is historic for its worship of a black meteorite for which Elagabalus was high priest, that was known as the Stone of Emesa. This was supposed to be the Stone from the Sun God, which actually played a central role in the region for nearly 2000 years of various religious beliefs. The exact origin of the black stone of Emesa remains rather obscure, and it most likely fell to the Earth at least during the 2nd Century AD and possibly before since there was evidence of a priesthood that extended well before the 3rd Century.

The destiny of this particular meteorite was closely intertwined with that of a dynasty of king-priests who had been nomads, Bedouins of the desert, before settling down in Emesa. It is possible that the stone fell somewhere else in the Middle East and was carried by the tribe before they settled in Emesa. However, the Roman Emperor Septimus Severus (193-211AD) married Julia Domna from Emesa. Severus was determined to create a dynasty and he depicted his family on his coinage regularly.This would eventually give rise to a hereditary claim to the throne of the Roman Empire by her side of the family centered in Emesa.

The destiny of this particular meteorite was closely intertwined with that of a dynasty of king-priests who had been nomads, Bedouins of the desert, before settling down in Emesa. It is possible that the stone fell somewhere else in the Middle East and was carried by the tribe before they settled in Emesa. However, the Roman Emperor Septimus Severus (193-211AD) married Julia Domna from Emesa. Severus was determined to create a dynasty and he depicted his family on his coinage regularly.This would eventually give rise to a hereditary claim to the throne of the Roman Empire by her side of the family centered in Emesa.Over time, this religious cult worshiping this Black Stone of Emesa became extremely famous and popular throughout the region. By the early 3rd century, the high priest known as Elagabalus from the family of Julia Domna became a Roman Emperor and the Stone of Emesa ended up being the chief deity of the Roman Empire by sheer force. This Black Stone was known under the title “deus invictus Sol Elagabalus,” the undefeatable sun which rises every day.

The Black Stone of Emesa was depicted on the coinage of Elagabulus (218 – 222AD) and upon his rise to the throne as an heir of Julia Domna, Elagabalus’ religious beliefs began to surface as a problem to say the least. The contemporary historian Cassius Dio suggests he murdered his adviser because he was forcing him to live “temperately and prudently” (Cassius Dio, Roman History LXXX.6) in order to try to get the Romans adjusted to the idea of having an oriental priest as emperor. His mother, Julia Maesa, according to Herodian, Roman History, went as far as to send a painting of Elagabalus in priestly robes to Rome and hung over a statue of the goddess Victoria in the Senate House. He was forcing his religion upon Rome, which did not sit very well to say the least. His homosexual behavior was also creating a scandal, which was much more acceptable in the East compared to Roman culture. The army did not take kindly to these homosexual tendencies. Revolts were breaking out even before he reached Rome.

Elagabulus brought the Stone of Emesa to Rome and built a temple there by the Palatine Hill he called the Elagabalium which was founded on the site of an earlier shrine to Orcus, a native Italic god of the underworld and a punisher of broken oaths. A portion of a capital from the Elagabalium was found in the Forum Romanum within the vicinity of the Palatine (R. Turcan, The Cults of the Roman Empire, 10th ed. [2008], p. 181, pl. 21). This capital confirms the appearance of the cult image and includes images of Minerva and Juno, providing important clues to the claims of Herodian (5.6) and Dio (80.12) that the emperor transported the Palladium to the Palatine in order to wed her to El-Gabal and later included a second spouse by bringing the cult statue of Juno Caelestis, the Punic Tanit, from Carthage. By doing so, Elagabalus was recreating at Rome the Emesene triad consisting of El-Gabal, Atargatis (Minerva), and Astarte (Juno Caelestis), thereby superseding the traditional Capitoline triad of Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva, the goddess of wisdom and the daughter of Jupter.

The legends of gods with always full of imagination. It was claimed that Jupiter impregnated the titaness Metis, but then recalled a prophecy that his own child would overthrow him. Fearing that their child would grow stronger and displace him to rule the Heavens, Jupiter swallowed Metis whole. The titaness forged weapons and armor for her child while within the Jupiter. Constant pounding and ringing by Minerva inside his head gave him a headache. To relieve the pain, Vulcan used a hammer to split Jupiter’s head and from the cleft emerged Minerva emerged fully grown and bearing her mother’s weapons and armor; quite a birth one would say. So Elagabalus was displacing this Triad of Jupter, Juno, and Minerva with his eastern El-gabal (replacing Jupiter), Caelestis (replacing Juno), and Atargatis (replacing Minerva). Clearly, Elagabalus sought to subordinate Jupiter to El-Gabal, and to promote the latter god’s rites, he then demanded the Senate to honor El-Gabal before all other gods when performing their traditional sacrifices. The Elagabalium was to be the new center of this worship in Rome. His reign was notorious for religious fanaticism, for cruelty, bloodshed and excesses of every description, and there was general satisfaction when, on March 6th, 222AD, Elagabalus and his mother Julia Soaemias were murdered in the praetorian camp. Their bodies were dragged through the streets of Rome and thrown into the Tiber. He was one of the most hated emperors because he tried to impose his religion upon all of Rome by force.

The Stone of Emesa was respected and sent back to Emesa. It appears in history once again on the coinage of another high priest who attempts the same path to the throne. When the Christians came to power, they destroy many objects. The Stone of Emesa was smashed. Smaller fragments survived in the region and were still worshiped.

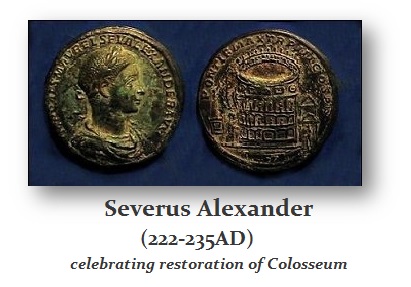

Elagabalus was succeeded by his cousin Severus Alexander (222-235AD). He wasted no time undoing the religious machinations of Elagabalus. To advertise that religion was restored, he issued coins depicting the dedication of Elagabalus to Jupiter. He issued coins depicting the restoration of the Temple of Jupiter in silver denarii and the bronze sesterius pictured above as well as medallions. Severus Alexander was so open-minded, he wanted to allow the Christians to establish their temple in Rome as well. He was persuaded against that by the majority who did not accept the idea of just one God. They had gone through hell with Elagabalus and were not about to tolerate another Eastern cult.

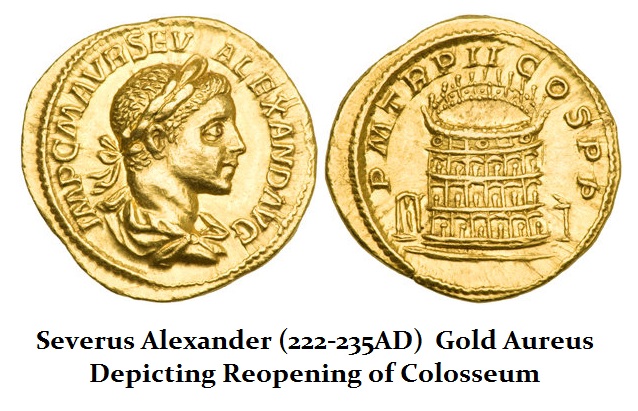

Severus Alexander (222-235AD) also issued coins announcing the restoration of the Colosseum was complete. On the day of the Vulcanalia, August 2nd, 217AD, a fire devastated most of the Colosseum and of the surrounding area. The Colosseum burned for several days and there was nothing left but its skeleton structure. The repairs began under Emperor Macrinus (217-218AD) and took about 30 years to complete since it was virtually reconstructed. When Several Alexander came to power in 222AD, the Colosseum was again inaugurated and dedicated to the gods. Coins were issued in gold, silver and bronze to announce the dedication.

Severus Alexander (222-235AD) also issued coins announcing the restoration of the Colosseum was complete. On the day of the Vulcanalia, August 2nd, 217AD, a fire devastated most of the Colosseum and of the surrounding area. The Colosseum burned for several days and there was nothing left but its skeleton structure. The repairs began under Emperor Macrinus (217-218AD) and took about 30 years to complete since it was virtually reconstructed. When Several Alexander came to power in 222AD, the Colosseum was again inaugurated and dedicated to the gods. Coins were issued in gold, silver and bronze to announce the dedication.

The third major structure announced on the coinage of Severaus Alexander was the Nymphaeum located in Piazza Vittorio Emanuele at a fork between the Via Tiburtina and the Via Labicana in Rome. Because the Romans invented concrete, a substantial portion of this monument remains. The construction in 226AD was brick-faced concrete. The fountain is reconstructed as a two-storied façade with a wide central niche and arched openings on each side. The overall appearance remains one of a triumphal arch. Statues indeed occupied the niches. Two such sculptures known as the “Trophies of Marius” which was removed by Pope Sixtus V in 1590 and still survives atop the staircase leading up to the Piazza Campidoglio. They were recycled from an earlier triumphal monument built by Domitian. The Nymphaeum was connected to the end of the aqueduct into Rome which was built inside an imperial villa at the time of Emperor Alexander Severus (222 – 235 AD).

The third major structure announced on the coinage of Severaus Alexander was the Nymphaeum located in Piazza Vittorio Emanuele at a fork between the Via Tiburtina and the Via Labicana in Rome. Because the Romans invented concrete, a substantial portion of this monument remains. The construction in 226AD was brick-faced concrete. The fountain is reconstructed as a two-storied façade with a wide central niche and arched openings on each side. The overall appearance remains one of a triumphal arch. Statues indeed occupied the niches. Two such sculptures known as the “Trophies of Marius” which was removed by Pope Sixtus V in 1590 and still survives atop the staircase leading up to the Piazza Campidoglio. They were recycled from an earlier triumphal monument built by Domitian. The Nymphaeum was connected to the end of the aqueduct into Rome which was built inside an imperial villa at the time of Emperor Alexander Severus (222 – 235 AD).

No comments:

Post a Comment