Posted Dec 26, 2018 by Martin Armstrong

The German Hyperinflation was by NO MEANS about inflation created by an increase in the money supply under the Quantity Theory of Money (QTM). Today, Angela Merkel has forcefully imposed Austerity upon the whole of Europe because she really does not understand what even caused the hyperinflation. It was at the Palace of Versailles outside Paris when Germany signed the Treaty of Versailles on June 28th, 1919 with the Allies, officially ending World War I. AT that time, the English economist John Maynard Keynes attended the peace conference. However, Keynes left in protest of the treaty becoming the first outspoken critic of what would prove to be the most punitive agreement that only set the stage for World War II and the rise of Adolf Hitler in 1933.

John Maynard Keynes wrote in his The Economic Consequences of the Peace, which he published in December 1919, that the harsh war reparation payments and other harsh terms that they were to impose on Germany by the treaty would lead to the financial collapse of the country. Keynes further warned that this Treaty would result in serious economic and political repercussions on Europe and the world as a whole. The political trend at the time refused to listen. This was all about punishing Germany.

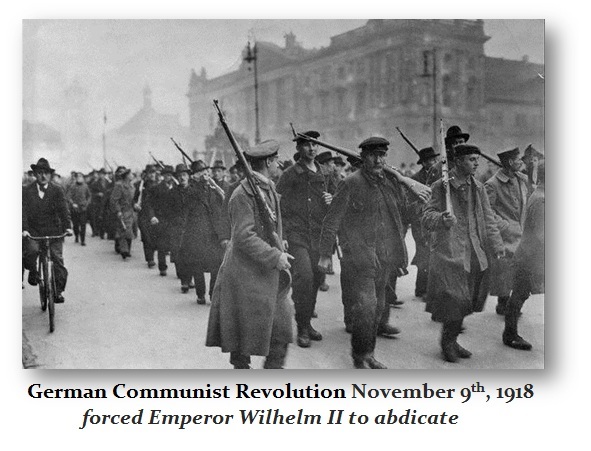

We must also understand that wars are created by politicians – not the people. Prior to the Treaty of Versailles signed in June 1919, there was the German Communist Revolution which began the Weimar Republic. It was this 1918 German Communist Revolution which was inspired by the 1917 Russian Revolution that resulted in the overthrown of the monarchy in Germany ending the Emperors and the king of Prussia. The revolutionary period lasted from November 1918 until the adoption in August 1919. But what also seems to be omitted from many accounts taught in school, is the simple fact that the German government interfered in the Russian Revolution and was instrumental in creating the Russian Revolution.

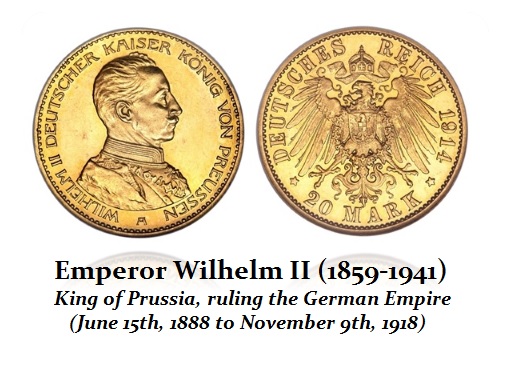

We must also understand that wars are created by politicians – not the people. Prior to the Treaty of Versailles signed in June 1919, there was the German Communist Revolution which began the Weimar Republic. It was this 1918 German Communist Revolution which was inspired by the 1917 Russian Revolution that resulted in the overthrown of the monarchy in Germany ending the Emperors and the king of Prussia. The revolutionary period lasted from November 1918 until the adoption in August 1919. But what also seems to be omitted from many accounts taught in school, is the simple fact that the German government interfered in the Russian Revolution and was instrumental in creating the Russian Revolution. The German Emperor Wilhelm II Imperial Government actually feared that Russia would enter World War I. The rising communist movement in Russia was anti-war. Germany saw a chance for victory in Europe if it kept Russia out of the war. Hence, Germany supported the Communist anti-war sentiment of the Bolsheviks in Russia. Germany permitted Vladimir Lenin (1870-1924) to travel in a sealed train wagon from his place of exile in Switzerland through Germany, Sweden, and Finland to Petrograd. Since the start of the February Revolution in Russia, Lenin was trying to figure out a way to get back into Russia. Germany aided his return assuming he was anti-war and would thus keep Russia out of World War I. Lenin returned to Russian on April 16th, 1917. Within months of arriving, Lenin led the October Revolution in Russia and the Bolsheviks seized power and indeed Russia withdrew from the world war. According to Leon Trotsky, the October Revolution would not have succeeded without Lenin.

The German Emperor Wilhelm II Imperial Government actually feared that Russia would enter World War I. The rising communist movement in Russia was anti-war. Germany saw a chance for victory in Europe if it kept Russia out of the war. Hence, Germany supported the Communist anti-war sentiment of the Bolsheviks in Russia. Germany permitted Vladimir Lenin (1870-1924) to travel in a sealed train wagon from his place of exile in Switzerland through Germany, Sweden, and Finland to Petrograd. Since the start of the February Revolution in Russia, Lenin was trying to figure out a way to get back into Russia. Germany aided his return assuming he was anti-war and would thus keep Russia out of World War I. Lenin returned to Russian on April 16th, 1917. Within months of arriving, Lenin led the October Revolution in Russia and the Bolsheviks seized power and indeed Russia withdrew from the world war. According to Leon Trotsky, the October Revolution would not have succeeded without Lenin.

With the success of the October Revolution in Russia and the Dream of a new Marxist Utopia, the Germans entered into a civil war and invited Lenin to please take Germany. Clearly, the scheme of the Imperial German government had backfired. It not only was instrumental in creating the Soviet Union by turning over Russia’s socialist transformation decisively into the hands of the Bolsheviks, its plan led to the overthrow of its own hold on power. This is all recorded in contemporary newspapers (see New York Times Nov 11, 1918).

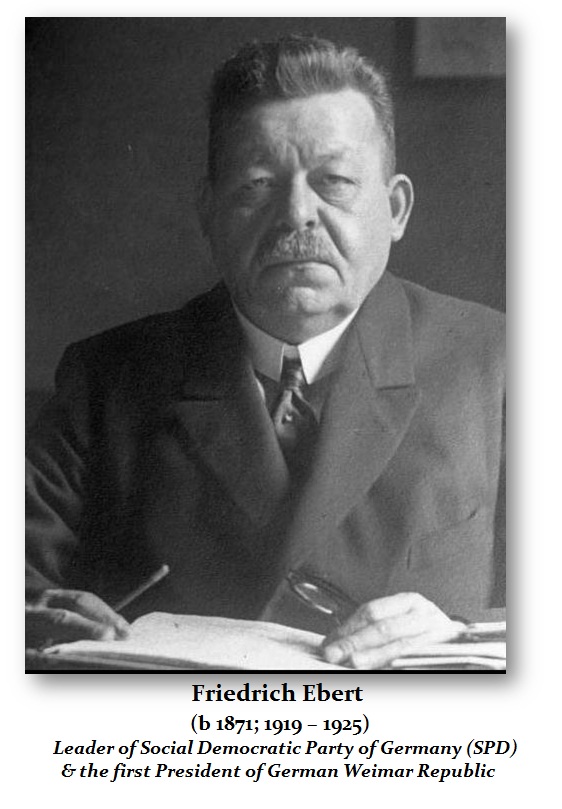

The Prussian Emperor Wilhelm II (1859-1941) found himself in the midst of troubling economic and social disorder. A series of mutinies by German sailors and soldiers undermined Wilhelm II’s government and he lost the support of his military which enabled the German people to revolt. Wilhelm II was forced to abdicate on November 9th, 1918. The very following day, a provisional government was announced composed of the Social Democratic Party (SDP) and the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (USDP). To this day, the SDP has remained as a major part against all opposition. Then in December 1918, German elections were held for a National Assembly with the goal of creating a new parliamentary constitution. On February 6th, 1919, the National Assembly met in the town of Weimar and formed the Weimar Coalition. They also elected SDP leader Friedrich Ebert (1871-1925) as President of the Weimar Republic who served from 1919 until 1925.

The Prussian Emperor Wilhelm II (1859-1941) found himself in the midst of troubling economic and social disorder. A series of mutinies by German sailors and soldiers undermined Wilhelm II’s government and he lost the support of his military which enabled the German people to revolt. Wilhelm II was forced to abdicate on November 9th, 1918. The very following day, a provisional government was announced composed of the Social Democratic Party (SDP) and the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (USDP). To this day, the SDP has remained as a major part against all opposition. Then in December 1918, German elections were held for a National Assembly with the goal of creating a new parliamentary constitution. On February 6th, 1919, the National Assembly met in the town of Weimar and formed the Weimar Coalition. They also elected SDP leader Friedrich Ebert (1871-1925) as President of the Weimar Republic who served from 1919 until 1925.

It was Friedrich Ebert who had to deal with the Treaty of Versailles. When the terms became known on May 7th, 1919, the German people rose in protest. Ebert himself did denounce the treaty as “unrealizable and unbearable” yet he understood that Germany was not allowed to negotiate nor reject the treaty. Ebert even asked Hindenburg if the army could put up a defense if the Allies renewed hostilities. Hindenburg said that the army was not capable of resuming the war even on a limited scale. Ebert then advised the National Assembly to approve the treaty, which it did by a large majority on July 9th, 1919.

The Treaty of Versailles commanded Germany to reduce its military, take responsibility for the World War I, relinquish some of its territories and pay exorbitant reparations to the Allies. It also prevented Germany from joining the League of Nations at that time. Thus, the treaty punished the German people for the sins of its government. Indeed, the military created World War I for it is generally accepted that Wilhelm II was largely just a ceremonial figurehead. During the Sarajevo crisis with the assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria on June 28th, 1914, he was Wilhelm’s friend and he offered to support Austria-Hungary in crushing the opposition who assassinated the Archduke. Wilhelm went on his annual cruise of the North Sea July 6th, 1914. Wilhelm returned to Berlin on the 28th of July that year and eagerly read a copy of the Serbian reply. Wilhelm wrote his comment on it:

“A brilliant solution—and in barely 48 hours! This is more than could have been expected. A great moral victory for Vienna; but with it every pretext for war falls to the ground, and [the Ambassador] Giesl had better have stayed quietly at Belgrade. On this document, I should never have given orders for mobilization.”

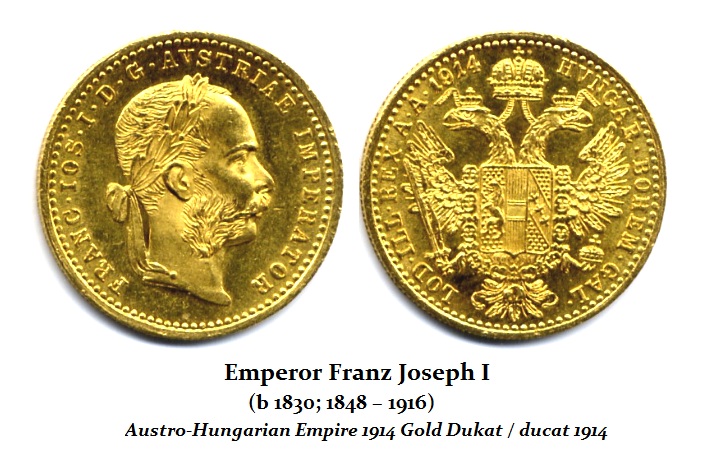

Wilhelm did not know at the time that the military had convinced the Emperor of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Franz Joseph I (b 1830; 1848 – 1916), to sign a declaration of war against Serbia. As a direct consequence, Russia began a general mobilization to attack Austria in defense of Serbia. Wilhelm wrote a lengthy commentary containing his observations:

Wilhelm did not know at the time that the military had convinced the Emperor of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Franz Joseph I (b 1830; 1848 – 1916), to sign a declaration of war against Serbia. As a direct consequence, Russia began a general mobilization to attack Austria in defense of Serbia. Wilhelm wrote a lengthy commentary containing his observations:

“… For I no longer have any doubt that England, Russia and France have agreed among themselves—knowing that our treaty obligations compel us to support Austria—to use the Austro-Serb conflict as a pretext for waging a war of annihilation against us … Our dilemma over keeping faith with the old and honourable Emperor has been exploited to create a situation which gives England the excuse she has been seeking to annihilate us with a spurious appearance of justice on the pretext that she is helping France and maintaining the well-known Balance of Power in Europe.”

In school, I remember being taught that World War I was the result of treaties among governments which then force one to come to the aid of another. Clearly, the Treaty of Versailles set the stage for World War II by its very crushing terms that nobody would be able to meet. The Treaty of Versailles set out a plan for reparations to be paid by Germany requiring to them to pay 20 billion gold marks, as an interim measure, with the final amount to be decided upon at later date. In 1921, the London Schedule of Payments set the German reparation figure at 132 billion gold marks divided into various classes, of which only 50 billion gold marks were required to be paid.

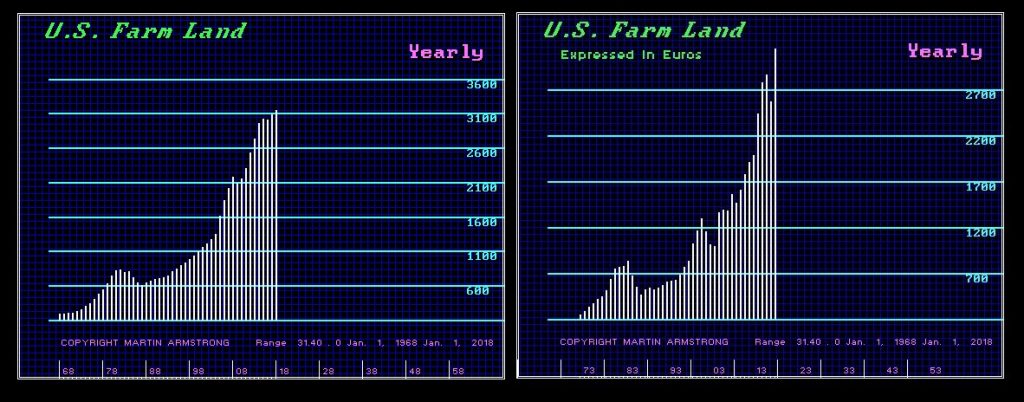

Meanwhile, the industrialists of Germany’s Ruhr Valley lost their factories in Lorraine. Germany had seized Lorraine back in 1870 and now this was to also part of the demands be returned to France. There was also an occupation of the Ruhr industrial area by France and Belgium. The Germans affected by the Treaty and the seizure of their property by France and Belgium now demanded hundreds of millions of marks as compensation from the German government and they paid the Ruhr Valley industrialists for their losses. This also contributed to the German Hyperinflation crisis and it effectively reduced the ability of the German economy to recover.

While the narrow neo-classical economic theory, hyperinflation is rooted in a deterioration of the monetary base, there is little attention paid to the collapse in public confidence that there is a store of value that the currency will be able to command later. Hence, people do not save and the velocity of money increases as people attempt to spend it as fast as they get it. There is a perceived risk of holding currency which rises dramatically at the core. Interest rates rise because they are the premiums people expect in the future when loans are repaid to make a profit. The hyperinflation that was set in motion by the Treaty of V was not limited to Germany. We also saw hyperinflations that I defined as a sharp and sudden doubling in prices (50% decline in the purchasing power of a currency) is less than three months in Austria and Hungary as well during this same period. In the case of Austria, hyperinflation began in October 1921 and continued into September 1922. In Hungary, the hyperinflation unfolded between March 1923 and February 1924. Philip Cagan’s (1956) The Monetary Dynamics of Hyperinflation widely accepted a definition which defines it as a price-level increase of at least 50% per month. However, even Cagan had to make exceptions because this cannot be defined precisely as some percent that is crossed will result definitively in hyperinflation. Therefore, the accepted definition remains rather vague and ill-defined.

In the case of Austria. here there was a separate treaty known as the Treaty of St. Germain which declared that the Austro-Hungarian Empire was to be dissolved. Under article 177 Austria, along with the other Central Powers, accepted responsibility for starting the war. The new Republic of Austria was to then consist of most of the German-speaking Danubian and Alpine provinces in former Cisleithania. Hungary was now split and Austria was commanded to recognize the independence of Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Poland, and the Kingdom of Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs. The Treaty of St. Germain also included ‘war reparations’ of vast sums of money that could also never economically be paid.

In the case of the Austrian Hyperinflation, the foreign-exchange value of the Austrian crown reflected the catastrophic depreciation of this event. In January 1919 one dollar could buy 16.1 crowns on the Vienna foreign-exchange market; by May 1923, a dollar traded for 70,800 crowns. According to the provisions of the Treaty of St. Germain, the newly created Republic of Austria had to overstamp the old paper money of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire still circulating in its territory, then had to replace the overstamped banknotes with new ones, and finally had to introduce an entirely new currency. To complete the first step, the circulating banknotes had to be overstamped with the inscription DEUTSCHÖSTERREICH, and new banknotes were also issued with this feature. Later, still under the name Oesterreichisch-ungarische Bank, banknotes were printed using the German-language clichés on both sides yet still displayed the DEUTSCHÖSTERREICH inscription. From 1920 onward, a new stamp appeared on banknotes: “Ausgegeben nach dem 4. Oktober 1920”. Next, in 1922 a new series of Krone banknotes was introduced with a completely new design to complete the second step. This series contained 1 Krone, 2, 10, 20, 100, 1000, 5000, 50 000, 100 000 and 500 000 Kronen, later 10 000 Kronen (1 000 000 Kronen was planned but not issued). Finally, in 1925, as the third step was to issue a new series of Austrian Schilling banknotes.

During this period, the printing presses worked night and day churning out the currency. At the meeting of the Verein für Sozialpolitik (Society for Social Policy) in 1925, Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises told the audience:

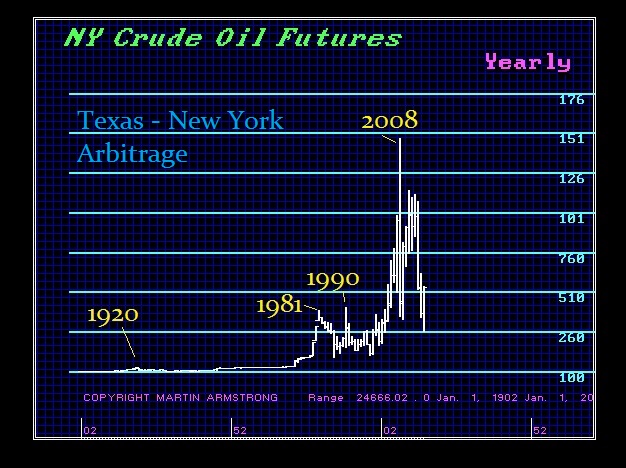

During the first five years after World War I, coal was scarce in Europe. France sought coal for its steelmakers from Germany. But the Germans needed coal for home heating and for their own steel industry, having lost many of their steel plants in Lorraine to the French. As a means of protecting their own growing German steel industry, the German coal producers—whose directors also sat on the boards of the German state railways and German steel companies—began to leverage high costs though shipping rates on coal exports to France.[3]

During the first five years after World War I, coal was scarce in Europe. France sought coal for its steelmakers from Germany. But the Germans needed coal for home heating and for their own steel industry, having lost many of their steel plants in Lorraine to the French. As a means of protecting their own growing German steel industry, the German coal producers—whose directors also sat on the boards of the German state railways and German steel companies—began to leverage high costs though shipping rates on coal exports to France.[3]

In early 1923, Germany defaulted on its war reparations payments and German coal producers refused to ship any more coal across the border. In response to this, French and Belgian troops occupied the Ruhr River valley inside the borders of Germany in order to compel the German government to continue to ship coal and coke in the quantities demanded by the Versailles Treaty, which, Germany which characterized as onerous under its post war condition (60% of what Germany had been shipping into the same area before the war began).[4]

This occupation by the French military of the Ruhr, the centre of the German coal and steel industries outraged the German people. They passively resisted the occupation, and the economy suffered, contributing further to the German hyperinflation.

Hyperinflation thus unfolded in Germany because those with money saw what Lenin had done in Russia and sent whatever wealth they had to other places, particularly the United States. They got their wealth out through using foreign coins, but also collectibles such as stamps and coins in particular. By the end of World War II, most German rare stamps and coins were actually in the United States and were slowly making their way back to Germany during the 1960s and 1970s.

The Weimar Republic then just printed money to pay reparation payments and the entire system collapsed.

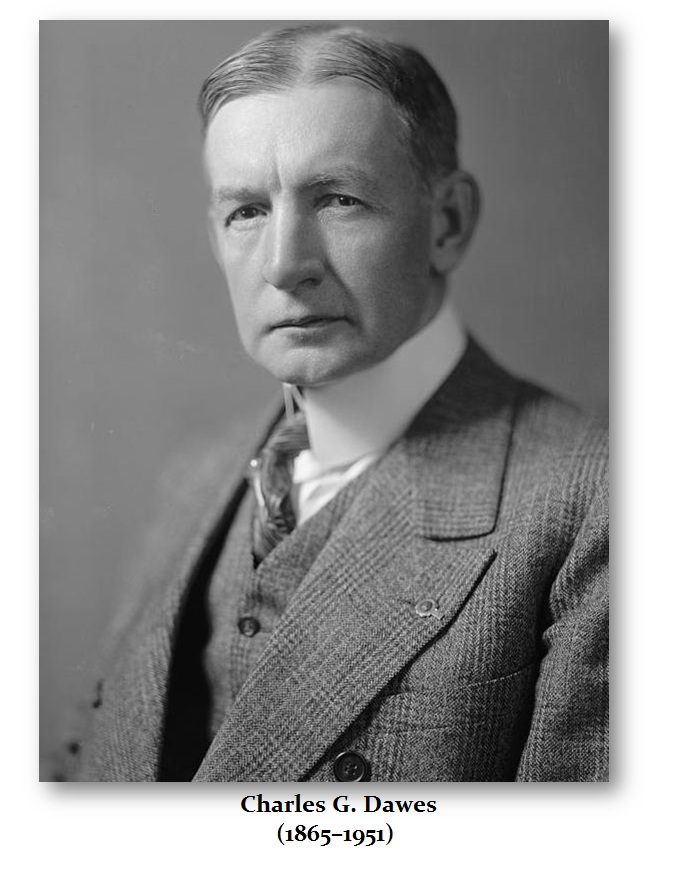

The Dawes Plan (as proposed by the Dawes Committee, chaired by Charles G. Dawes) was an initial plan in 1924 to resolve the World War I reparations that Germany had to pay, which had strained diplomacy following World War I and the Treaty of Versailles.

The Dawes plan provided for an end to the Allied occupation, and a staggered payment plan for Germany’s payment of war reparations. Because the Plan resolved a serious international crisis, Dawes shared the Nobel Peace Prize in 1925 for his work.

It was an interim measure and proved unworkable. The Young Plan was adopted in 1929 to replace it